Whilst I was at Liverpool Hope University my main topic of focus was Land Art. Researching this topic came to inform my own artwork.

I was always drawn to this area of study because I found it so fascinating. Land Art emerged in the United States of America in the late 1960s during an era of radical change. The movement involves working within the landscape – often in deserted areas far away from civilisation – and rearranging the natural state of the Earth.

Various terms refer to the movement, the most popular being ‘Earthworks’ – a term coined by Land Art’s most famous artist Robert Smithson.

It is often men that are associated with the movement, with female artists unheard of or unknown about, even though there was a considerable number of women working with the land during the late 1960s and continuing into the 1970s.

Land Art Gender Imbalance

Through my writing I wanted to study this gender imbalance. Feminism has always been a big part of my life, in every aspect, and I was curious to figure out why women were absent from the history pages of Land Art.

I want to research the gender imbalance which occurred within the Land Art movement from its beginning years. In the initial exhibitions in 1968 and 1969, it was only male artists who were featured. And continuing up until recent years, women are still the less-discussed sex in the books and articles reviewing the movement. In this text I will examine the gender imbalance within the movement, and also within the writing of the Land Art histories.

I want to examine why there had been a prioritisation of the work made by men, in comparison to women. It is particularly important to look at Land Art in this way as there were many female artists working within the movement. Yet we still do not know much about their work despite the impact of feminism on art historical approaches.

Rewriting the History of Land Art

Whilst assessing my research at university, I took a revisionist approach to my chosen topic by demonstrating that the work made by female artists was important to Land Art. I chose to study both the reception and production of Land Art because gendered histories of art are created at the level of reception.

To provide a well-informed discussion I will review a wide variety of Land artists, rather than taking a case study approach. This is to prove the hypothesis that there were many women working within the movement, making work akin to their male counterparts. Yet their work has generally gone unnoticed in the written histories.

The Rise of Feminism

Throughout all periods of art there has been a gendered imbalance due to patriarchal society. This male precedence occurred until the mid-twentieth century when, due to the rise of feminism, women began to question the roles of females within society.

It was during the beginning of the second wave feminist period that the Land Art movement came about. Women until this point in history had always been the devalued sex in patriarchal society. Gender equality was still a new concept at this point and obviously affected the renown of female artists.

The first phase of organised feminist activity begins in the nineteenth century (first wave) and is revived in the early 1960s (second wave). During the first phase of feminism, women strived to break free from patriarchal society and aimed to create an egalitarian order (Foster et al. 2011 p. 164).

It is during the second wave of feminism that women attempted to participate in the male-dominated art world. Scholarship at this time discussed the fundamental differences between men and women, the commonalities unique to women. From this, various responses were developed regarding the subordination of women in historical and contemporary society.

Women and Nature

Although there is a relative lack of literature available about female Land artists, there is an important body of feminist literature dealing with the relationship between women and nature. Women have historically been associated as being closer to nature than men, therefore they would logically seem to be the natural Land artists.

In male-dominated Western culture, women’s knowledge and creativity has been linked with their bodies and sexual reproductive organs, symbolically making them closer to nature. Whilst men, who are free from such bodily restraints, are closer to culture.

It was Sherry Ortner (1972, cited in Robinson 2001, p. 17) who hypothesised that women tended to be identified with nature.

Whilst men – who were free from the physical reproductive changes and could therefore pursue intellectual activities - were assumed to be more cultural.

This association of women with nature is not biologically ‘natural’ Ortner argues. However, it is merely the lesser valued symbolic category to culture in the social order. Ortner tells us that in every society throughout history, women have always been the subordinated sex. Therefore, because of patriarchal society values, it is ‘natural’ to society for culture (men) to oppress nature (women).

Lack of Information

During my research at university, I found that the information available regarding female artists is extremely sparse in comparison to the leading male figures. The topic is under-researched and therefore there is a distinct lack of texts available specifically discussing female artists and gender issues of both masculinity and femininity within Land Art. Surveys discussing the movement in recent literature generally discuss the main (male) figures in the movement – Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, Richard Long, Christo, and so on – and dedicate a small section (or no space at all) to female artists.

Much of the information gained about these artists have been pieced together from a range of sources. However, with retrospective exhibitions since 2008 featuring female artists, new research has been encouraged.

Land Art Information Sources

Useful sources for general information regarding Land Art include Kastner and Wallis’ (1998) anthological survey book, Land and Environmental Art, which broadly summarises the movement. However, the disproportionate amount of information available regarding female and male artists is clear throughout the text. The work made by men is discussed thematically, whereas women are discussed together in a small section, regardless of the genre of their work.

Nancy Thebaut and Elizabeth Upper in their article ‘Earth Movers: Quaking up Land Art’s Legacy of Feminism’ (2010), however, offer discussion regarding the gender inequalities within the movement which caused female artists to be overlooked. A limiting factor of this article, however, is that the authors only briefly touch upon many themes and aspects regarding women working with the Land, therefore there is not an extensive amount of detailed information in the text.

In ‘Excavating Land Art by Women in the 1970s’ Suzaan Boettger discusses the fact that a significant re-examination of the Land Art movement needs to be undertaken to give female artists the recognition that they equally deserve.

The First Land Art Exhibitions

The first display of Land Art in 1968, Earth Works, located at the Dwan Gallery in New York, featured only male artists. Land Art exhibitions in the following year – Earth Art at the Andrew Dickson White Museum and Ecological Art at the Museum of Modern Art, both in New York in 1969 – also presented male-only shows (Kastner and Wallis 1998 p.14).

The works made by Land artists were not overtly influenced by exterior political issues of the time. The Cold War was at its height and casualty numbers in Vietnam had peaked. Martin Luther King Jr and Robert Kennedy were both assassinated, and there were various anti-war and civil-rights demonstrations taking place across the country. The new post-war Land Art movement reflected the conflicted and changing socio-cultural conditions of its time. The artists rejected the traditional norm of displaying work inside a gallery space, and brought about a new approach to making and seeing art (Tuffnell 2006 pp. 12-13).

The Exclusion of Women From Land Art Exhibitions

Although I have previously noted that women would appear to be the ideal Land artists due to their supposed connection with nature, this cultural essentialist association and sexist prejudice can be seen as one determining factor of women’s exclusion not only from the initial Land Art exhibitions, but from the art world as a whole. Men were seen to be the intellectually superior species to women as they were associated closer with the mind than the body. It was men that were the artists displayed in the initial Land Art exhibitions, and are still the only sex generally associated with the movement.

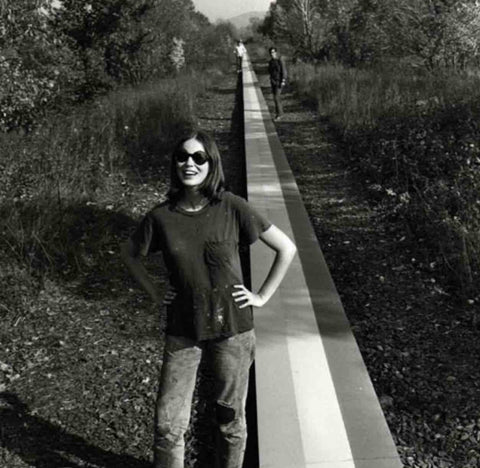

During the initial years of the Land Art movement, American artist Patricia Johanson was making work that fit the Earthworks theme. In 1966, the artist made William Rush, a 200- foot long outdoor sculpture made up of painted beams.

Although women were not included in the initial Land Art exhibitions, many are featured in recent comprehensive retrospective exhibitions of the movement.

Johanson’s 1,600-foot long outdoor work Stephen Long, made in 1968, was included in the 2012-13 exhibition Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974, hosted at Haus der Kunst in Germany. It was in 1968 that Johanson began making site-specific sculptures in nature out of wood or cement.

Many female Land artists who I will discuss throughout this dissertation – Mary Miss, Alice Aycock, Patricia Johanson, and Nancy Holt – are often grouped together in survey books for little more unifying reason than their gender. It is noted by Schwartz (2010 p. 417) that the work by Miss, Aycock and Winsor never achieved the same level of success – in terms of fame recognition and financial selling price – as their male contemporaries. Miss and Aycock gained recognition during the late 1960s when they were politically active within the emerging women’s movement. Their work, however, did not address issues of gender equality; therefore, they were wary of associating their work with the feminist movement (Schwartz 2010 p. 415).

When reviewing the male-only panel of artists included in the first Earthworks exhibition, New York writer Don McDonagh (1968 p. 3) referred to “Art’s New Earthmen”, discussing the “encounters between man and nature”. McDonagh was using the then normal term of ‘man’ to stand in for the universal ‘human’. Roach discusses how referring to the earth as “Mother”, or in McDonagh’s case “Earthmen”, affects how society thinks regarding gender. Feminist literature has now drawn our attention to such terms masquerading as universal.

In the reviews of the time, the omission of female artist participants in the exhibitions is not mentioned as sexist, and gender inequality was only beginning to be discussed at this point within the art world.

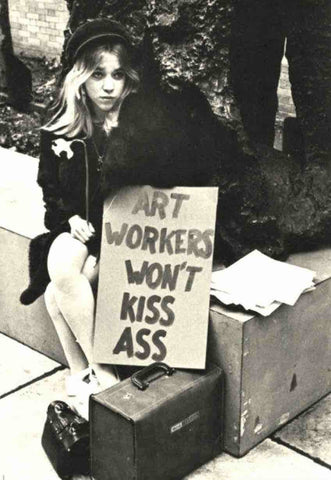

Second wave feminism began in the late 1960s and it wasn’t until 1969 that women’s exclusion from art exhibitions was addressed at “The Museum’s Relationship to Artists and to Society” conference in New York (Lippard 1970 p. 173).

Writing for New York’s Village Voice, John Perreault (1968 p. 17) observed that “Most of the works in ‘Earthworks,’ aside from the fact that they all have something to do with earth, are quite different from each other.” This is an issue which I will refer to later in this essay. The work of men in Land Art exhibitions is generally seen as varied, and then grouped by theme, medium or concept. However, the work of women is generally always grouped together – regardless of its content – due to the gender of its makers.

Patronage

Private Funding

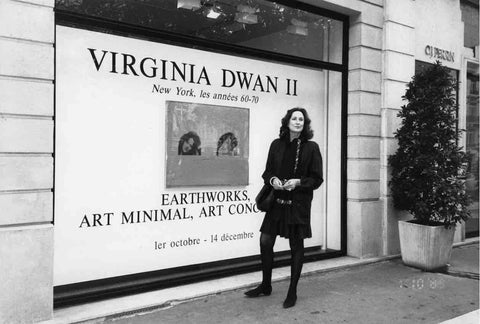

Making Land Art was extremely costly and therefore relied on wealthy patrons and private foundations. The main patrons at this time were gallery owner and art dealer Virginia Dwan, Heiner Friedrich, The Dia Foundation, Robert Scull, and later on in the movement Douglas Christmas. As issues of gender equality were only beginning to be addressed at the this time, and due to the sheer task of creating Land Art, all of these patrons invested funding in male artists (Boettger 2002 p. 148). Boettger (2004 no pagination) notes that Virginia Dwan was particularly selective when it came to funding projects or featuring artists in her exhibitions. No women had a solo show at her New York gallery or was a beneficiary of her patronage (however, a small percentage of women were occasionally represented in group exhibitions).

This selective aspect of Dwan’s (and other key patrons) funding and gallery representation decisions, according to Boettger, was due to the social conventions at the time that excluded female artists. However, in the early 1970s, Alice Aycock, Agnes Denes, Nancy Holt, Mary Miss and Michele Stuart began to make environmental works which were funded by institutional commissions from museums, universities and major periodic international exhibitions (Boettger 2004 no pagination).

Gender Inequality in The Art World

A further reason for the lack of female Land artists in the early years of the movement was due to their disadvantage to men in terms of gallery representation. At the 1969 conference “The Museum’s Relationship to Artists and to Society”, issues of gender equality began to be addressed within the art world. The fifth demand on the list for equality stated that “museums should encourage female artists to overcome centuries of damage done to the image of the female artist by establishing equal representation of the sexes in exhibitions and museum purchases and on selection committees” (Lippard 1970 p. 173). Women’s social and cultural roles were beginning to change.

Until this point in history it had been very difficult for a female artist to break into the man’s world of art. It was in September 1970 that the first Committee of Women Artists was formed, which began the development of the feminist art movement (Boettger 2002 p. 149).

Many Land works made by female artists during the early years of the movement, especially ones which didn’t cause large-scale changes to the land, were overlooked, as noted by Thebaut and Upper (2010 p. 38).

Although conducting an extensive literature search, it has been extremely difficult to find examples of prominent Land Art made by women during the years of the initial exhibitions. This may be due to the fact that women at this time simply were not yet making work that suited the aims of the Land Art movement, or that their work was overlooked due to their sex. The highest likelihood is that women were just as ambitious in their ideas as their male counterparts; however they were unable to secure adequate funding.

Judy Chicago - Atmospheres

From 1968 to 1974, American feminist artist Judy Chicago made a series of works within the landscape called Atmospheres. These works were performances attempting to “beautify” the landscape through the use of fireworks and coloured smoke, as opposed to bulldozers. By making Land Art with this method, Chicago stated that she had “reversed the desecration of the natural environment and the rape of the planet” (Malone 2013; Thebaut and Upper 2010 p. 40). Chicago’s initial aim for Atmospheres was to fill the Grand Canyon with smoke - a feat that would have rivalled her male counterparts. However, due to lack of funding, the artist had to work on a much smaller scale (Thebaut and Upper 2010 p. 41).

Atmospheres are relatively unknown, having little written about them. It is likely that these works were mostly ignored because of their ephemeral state and lack of permanent impact on the land. They only exist now in documentary photographs.

Although most Land works are generally only viewed through their documentary photographs, due to their remote locations, patrons at the time tended to invest in permanent impressions which would last on the landscape instead of temporary performance pieces.

We can now see how it was hard for women to break boundaries during this era. Women were denied funding due to gender inequalities and because the work they made was generally ephemeral, yet women had to make inexpensive (and therefore often ephemeral) works because of their lack of funding.

Rejecting Romantic Associations with Nature

With key patrons such as Virginia Dwan funding male-only projects, and including a male-only artist group in the Earth Works exhibition at the Dwan Gallery in New York (arguably what most people would associate to being the ‘birthplace’ of the movement, connecting many of the movements artists) it is clear to see why women are generally not associated with the movement.

It is significant that women were not included in the initial Land Art exhibitions. As I have previously stated, due to the stereotypical gendered affiliation it would seem that women would be the natural Land Artists. However, as the movement originated during the beginning years of second wave feminism, it is noted by Boettger (2004 no pagination) that female artists would have most likely actively rejected any romanticised association with nature.

The male artists would have also dismissed this. Boettger (2002 p. 208 and 220) notes both Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer openly renounced any idealized romantic or sentimental connection to the land. However, due to their lack of gendered affiliations with nature, they could work with the earth without provoking historical associations.

It is noted by Boettger (2002 p. 148) that being awarded funding was an issue for female Land artists, as the key patrons at the time favoured male artists.

This will have affected the limits of their ideas being realised. After Robert Smithson’s untimely and sudden death in a plane crash in 1973, and the economic recession during the mid-1970s which ended the post-war financial boom, the movement lost its main figurehead and much of its funding and gradually ended. Therefore, it was essential to be associated with the initial exhibitions in the first years of the movement as they defined the key artists and art works.

Moving Away from the Art Gallery Space

The importance of moving sculpture away from official art sites, such as gallery exhibitions and monumental buildings which house site-specific works, is highlighted by Robert Smithson (1972 p.947) in his essay Cultural Confinement. Smithson compares gallery spaces to asylums and jails, stating that art galleries and curators impose limits on art, neutralising and disengaging art from the outside world, declaring that “innovations are allowed only if they support this kind of confinement”.

Smithson is opposed to the idea of placing sculptural work within gardens or parks, stating that the work then lacks “ongoing dialect”, as the work becomes associated with “the ideal representation of the past”, therefore reinforcing political and social values that are not relevant to contemporary culture.

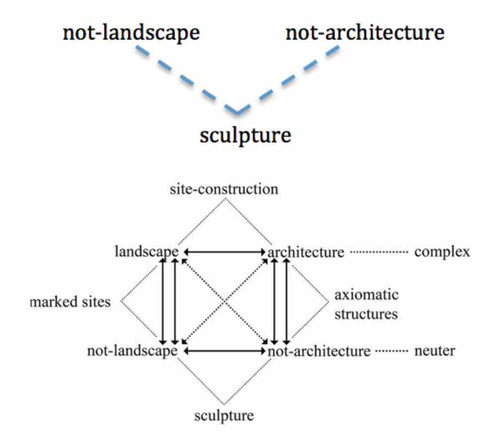

Sculpture in the Expanded Field

One text which I critically analysed during my time at University was the 1979 text Sculpture in the Expanded Field written by American art critic Rosalind Krauss (b.1941). The text was written retrospectively in response to the three-dimensional art forms which emerged in the 1960’s and needed categorising. Krauss’ intention of the text was to map the determinant structure of the ever expanding field of postmodern sculpture and develop a critical language on a periphery of terms to differentiate seemingly similar new artworks (1979 p.44).

Krauss begins the text by questioning what sculpture is, describing Modern sculpture as “the ideology of the new”, and a movement that is “infinitely malleable” and open to nearly any kind of medium.

The opposite term to sculpture within the expanded field is “site-construction”. This term, the complex of both “landscape” and “architecture”, refers to artworks which are located outside of the museum space, and are site-specific and integrated within the landscape – not merely placed on top of the landscape.

In a lecture at Yale University, Richard Serra (1990 p.1125) described site-specific works of art as “[becoming] part of the site and [restructuring] both conceptually and perceptually the organisation of the site”. Assuming forms which function to accentuate the language between the site and the work itself.

Douglas Crimp (1993 p.153), commenting on the work of Serra, states that “the work was conceived for the site, built on the site, had become an integral part of the site, altering the very nature of the site. Remove it and the work would simply cease to exist”.

Referring to the recent awareness of material use in art at the time of his 1969 essay, Situational Aesthetics, Victor Burgin (1969 p.884) describes the artist “not as a creator of new material forms but rather as a coordinator of existing forms”, a statement which well describes Krauss’ term of site-construction.

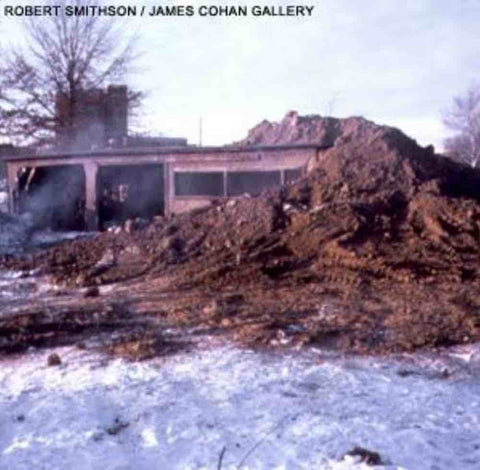

One example of site-construction given by Krauss is Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed, made in 1970 in Ohio.

This work, made by Smithson and a group of students at Kent State University, involves a woodshed which had been partially covered in a large pile of dirt. The dirt was piled on top of the shed until the structure began to crack, initiating an action which then continued to unfold over many years. This work fits in the category of site-construction as it is categorically a site-specific work – it cannot be moved from its original location – and the work becomes part of the landscape, or rather the work is the event of altering the landscape and therefore viewing the landscape in a different way once the work has been constructed (Krauss 1979 p.41).

The Work Becomes The Space

The final area of the expanded field described by Krauss looks at “axiomatic structures” - “axiomatic” meaning self evident. These works - “architecture” and “not-architecture” - are a transformation of space described by Krauss as being “some kind of intervention into the real space of architecture”. Meaning that the work is built into the space (Krauss 1979 p.41). The work is not an installation, nor a thing you can put into a space, instead it becomes the space.

An example of this would be Gordon Matta Clarke’s Splitting, made in 1974. In this structure, Clarke literally splits a house into two, altering, and therefore highlighting, the architecture to provide a new experience of the space, calling into question the social, historical and political implications behind the architecture and the work. Although Krauss’ intention of mapping out the expanded field was to dictate terms to differentiate new three-dimensional works, her vocabulary has generally not remained within art terminology. What Krauss describes as “axiomatic structures” is generally referred to in contemporary society as installation art.

Marked Sites

The term “marked sites” is explained within Krauss’ expanded field as being “landscape” and “not-landscape”. Marked sites can be described as altering the landscape through the use of natural materials. Therefore, as only landscape materials have been used, it is the landscape that we see. But it is not the landscape at the same time, as the natural landscape has been rearranged and is not naturally ordered in the particular ways that marked site artists employ.

Examples of marked sites would be Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, Agnes Denes’ Tree Mountain, and most earth works by Andy Goldsworthy.

As with site-construction works, marked sites are anti-gallery, rejecting the formal traditional art making and selling rules. These works are generally always made in extremely remote locations, opposing gallery systems which are (nearly always) located in populated cities

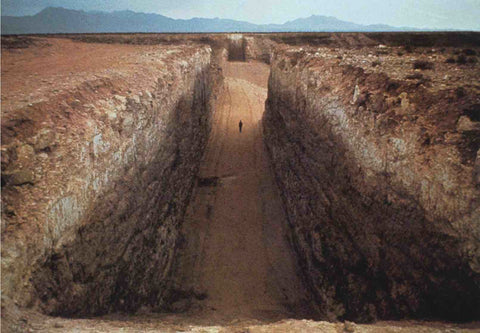

Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, made in Nevada, 1969, is a strong example of being a marked site. The work is made by the removal of earth, making free space within the natural landscape that was not there before.

Marked site works cannot be moved or sold as they are totally site specific to their place of creation. There is no such thing as a “neutral site”. However artists will generally choose “leftover sites which cannot be the object of ideological misinterpretation” so to avoid being assimilated with gallery institutions (Serra 1990 p.1126-7).

Rejecting Traditional Forms and Mediums of Object Making

In “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” Krauss illustrates through sequential, logical explanation and critical diagrams the collapse of disciplines formally associated with the making and function of sculpture that occurred in the transitional period of the 1960’s. Sculptors rejected the traditional forms and mediums of object making and reinvented the term, finding new ways to convey thoughts and ideas. In writing this essay, Krauss redefined the way in which we consider art today through her criticism of historicism, favouring empiricism instead as the way to analyse new modes of art making.

A Gendered Comparison of Male and Female Land Art

Through conducting my research at university I examined the differences and similarities in the ways male and female artists approached working with the land from 1968 until the end of the 1970s. Technique, practice, subject matter and overall visual aesthetics were areas I considered. Through the use of documentary photographs and primary texts, I reviewed the work of male and female Land artists. I examined the scale of the work, whether it is ephemeral or permanent, the location and how easily accessible the work is, and whether the work involves public participation. The purpose of this comparison was to demonstrate if there were any qualitative differences between the work of male and female Land artists in terms of themes and content.

I will be discussing only American female land artists in this section as there are no prominent British female Land artists. British artists Marie Yates and Phillipa Ecobichon both have work in the Arts Council Collection but it is not sufficiently documented to enable research through books or the internet. It is also not in suitable condition to be exhibited and viewed in a gallery. Other female artists working with the land are Susan Hiller, an American born artist who lives and works in the UK. And Joan Hills, a British-born artist who works as part of the Boyle Family as well as in her own right. Both of these artists were recently featured in the 2013-14 UK travelling exhibition Uncommon Ground: Land Art in Britain 1966-1979.

I will not be discussing either of these artists as there is significantly less material available in comparison to the American female Land artists to support my line of enquiry regarding their work, therefore my writing would have insufficient support.

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty

Possibly the most famous Land Art work ever created is Spiral Jetty, made in 1970 by Robert Smithson (1938-1973). This iconic work was built by moving 6,000 tons of land from Utah’s Great Salt Lake to create a 1,500 foot-long rock spiral. It took six days for Smithson and his team to create Spiral Jetty; an incredible feat for such a large work.

This work, although permanent, is subject to the weather cycles of nature: two years after Spiral Jetty was completed, the work disappeared entirely under water due to high tides and water rises (Boettger 2002 p. 204). Spiral Jetty was then only visible sporadically over the next thirty years until 2002 when the work re-surfaced due to a drought. The once-black basalt rocks had turned white at this point from salt encrustations, and the water surrounding the work developed a pink hue.

This happening would have pleased the artist (who died three years after Spiral Jetty’s completion) as in many of his writings he discussed entropy – the decay and renewal that naturally occurs in nature.

Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series

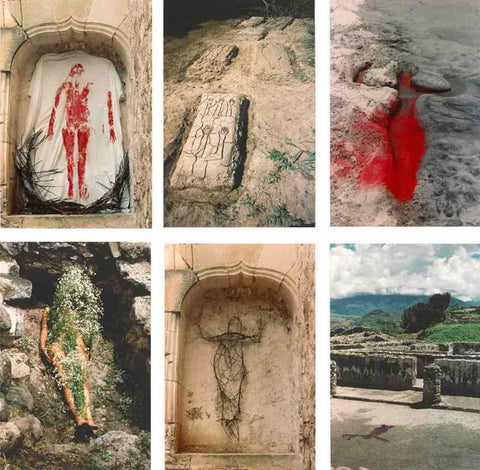

Although much work made by male Land artists during the 1960-70s was, like Spiral Jetty, grand in its scale and presence, there were artists who worked in a minimal style with very low impact on the land, choosing to interact with the land in less intrusive ways. From 1973-1980, Cuban-born artist Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) created the Silueta Series. This was a series of works which involved the artist imprinting her bodily form on the landscape, and then photographing the gradual happening or disappearance of the ephemeral Silueta.

Each Silueta would be gradually taken over by natural events by being burnt away, filled with water, blown away by the air or grown through by the earth (Boetzkes 2010 p. 50). It is noted by Land Art expert Ben Tufnell (2006 p.62) that during the end of the 1960s a new kind of landscape art emerged alongside the well-known monumental Earthworks – performance and body art. Mendieta was a leading figure in this branch of Land Art, with the Earth being the recipient of her performances and bodily imprints, allowing for analogies to be drawn between the two.

Minimal Impact on the Earth

Due to the rise of feminist activity in the 1960s, the literature produced in the 1970s examined the myths, histories and symbolism relating to woman as a ‘Goddess’, discussing the earth as a feminine entity. It is noted by Kastner and Wallis (1998 p. 34) that performances linking the earth to the body were often ritualistic in their approach, and the earth was often seen as being an intimate extension of the human body.

Through the relationship between the body and the Earth in Mendieta’s work, the artist touched upon issues of patriarchal culture (men having control of both women and land). The work was seen to be (whether intended by Mendieta or not) essentialist in itself, regarding the duality of men being closer to culture and women closer to nature.

Richard Long & Hamish Fulton

Other male artists who worked within the land applying minimal impact were British artists Richard Long and Hamish Fulton. Their work involves taking long walks through various parts of the world and leaving very little trace or impact of their journey on the land. For the purpose of the work, the walk in itself was the artistic act.

In 1967, Richard Long made the work A Line Made by Walking. This work is a photograph showing a field of grass in Wiltshire, England, with an ephemeral line made by Long from repeatedly walking up and down in a straight line. Whether Long’s work is the ephemeral act of walking, or the documentary photograph, is an interesting topic.

The ontology of performance is discussed by Peggy Phelan (p. 146) who states that “Performance’s only life is in the present” and that it cannot be recorded or documented, for once this happens the work becomes something other than a performance.

I agree with Phelan’s views that documentation is entirely different to a live act. However, documenting work was commonly practiced in Land Art. As so many of the works were inaccessible or ephemeral, the documentary films and photographs were the only way for most people to see the works. Both Smithson and Long worked in very different styles, yet both artists are considered to be two of the most highly regarded within the movement. I make this statement because I believe if it were a woman who made Long’s work, she would not have received the same recognition.

The walking process by Richard Long has a very low impact upon the environment and demonstrates an ecological sensitivity. The majority of work made by Long is ephemeral, which is made to be destroyed by nature.

British male Land artist, Hamish Fulton, describes himself as a ‘walking artist’ whose work involves interacting with the landscape through exploratory hiking experiences. In 1973, Fulton walked 1,022 miles over a period of forty-seven days across England and Scotland. These journeys are then presented in gallery exhibitions in the form of texts, photographs and books (Grand 2004 p. 129).

Another prominent British Land artist is Andy Goldsworthy.

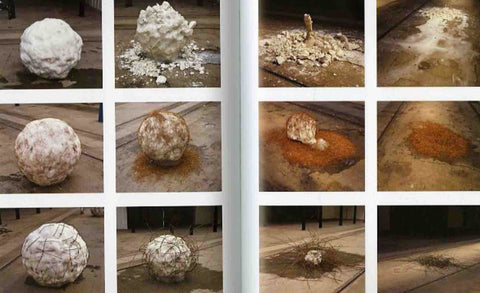

The work made by Goldsworthy is site-specific as it involves the natural found objects specific to a particular location. One of Goldsworthy’s most famous works is the ephemeral series of snowballs (pictured above) that were located in various locations across London. Inside each snowball various materials such as twigs, coloured chalk or pigment, pine needles and dogwood were hidden, and as each snowball melted the inner contents would slowly be revealed.

British vs. American Land Artists

It is interesting to briefly compare the working methods of the American (male) Land artists to the British: in 1970, when Robert Smithson was using bulldozers to drastically alter the earth to create Spiral Jetty, Richard Long was completing a ten- mile walk across Dartmoor, England (MOMA 2014).

American Land artists tended to employ the use of heavy machinery to create their monumental works, shifting the land to change it. Whereas British Land artists would generally avoid the use of mechanical equipment, taking a more gentle approach and choosing to work with what was available on the earth. American Land Art works were mass structures, whereas British works, in comparison, were much more minimal – purely conceptual in some cases - in their style and approach.

A notable similarity, however, is the use of simple shapes in the design of the works. Circles, lines, spirals, squares and other modest shapes are employed by all Land artists in their work. There are many variations of work made within the Land Art rubric which are accepted as part of the movement. Therefore there is no reason for the female participants of the movement’s work to be devalued in history due to lack of recognition.

Eco-Feminism

During the 1970s, ideas regarding environmental awareness and feminism were being brought together to create work sometimes referred to as Eco-feminist. These works often served such practical and functional needs that they were unrecognised as works of art. As the word ‘Eco-feminism’ linguistically brings together women and nature, the term is particularly prone to being associated with essentialism.

Bina Agarwal (1992 p. 120) notes that in Eco-feminist arguments “the connection between the domination of women and that of nature is basically seen as ideological, as rooted in a system of ideas and representations, values and beliefs, that places women and the nonhuman world hierarchically below men.”

This association in which Eco-feminism accepts the patriarchal concepts of women being closer to nature than men is critiqued by many feminist writers. Agarwal (1992 p. 122-3) criticises Eco-feminism for referring to women as a “unitary category” and failing to “differentiate among women by class, race, ethnicity, and so on”. Therefore ignoring any form of denomination for women except for gender. This statement is agreed with by Anne Archambault (1993 p. 21) who notes that Eco-feminism’s effectiveness is limited by the reinforced “patriarchal ideology of domination” which only strengthens the notion that natural biology is what determines the social differences between men and women.

Useful and Practical Land Art

The Land Art made by female artists has often been considered as being useful and practical: Kastner and Wallis (1998 p.15) note that many female artists who worked with the land tended to approach making art with a utilitarian approach. Everyday activities associated with being feminine - such as cleaning, washing, gardening, caretaking and nurturing - were explored through artistic means.

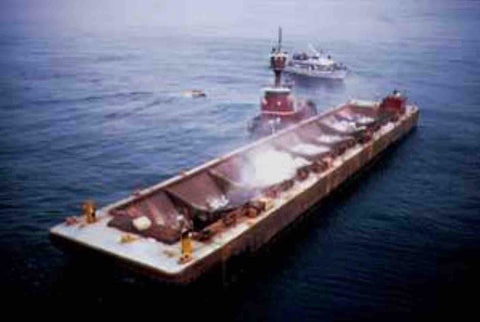

Ocean Landmark, conceived in 1978 by Canadian artist Betty Beaumont, is an underwater work on the floor of the Atlantic which is designed to recycle waste and establish a habitat for fish (Green Museum 2010).

The Lagoon Cycle, 1974-84, by married couple Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison is a series of seven artificial environments which nurture the environment to provide food for crabs, allowing them to breed to provide a source of food for humans (Stephens n.d).

Many of the environmentally aware Land Art works are made to last a long time to sustain communities. In ‘The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s’, Lucy Lippard (1980 p. 364) states that because the traditional art made by women has always been considered utilitarian, many feminists were “more willing than others to accept the notion that art can be aesthetically and socially effective at the same time.” The stance towards making useful works of art which can function to improve the environment, in the case of Land Art) can be seen to be adopted by some female Land artists - Agnes Denes, Patricia Johanson, Betty Beaumont and others - but not all.

Gendered Connotations

Female Land artists who approached the earth with environmental and social concerns were working “in a parallel yet markedly different way than [their] male analogue[s]” state Jeffrey Kastner and Brian Wallis (1998 p. 14). The artists who approached working with the land in an ecologically friendly way – Denes, Johanson, and Beaumont (amongst others) – are all known artists in their own right. However, as members of the Land Art movement, most are unheard of due to the sparse amount of critical writing available concerning their work.

These artists freely incorporated stereotypical feminine roles of caretaking (in this case, of the environment) into their work, and changed perceptions of exactly what could be considered a work of art (Kastner and Wallis p. 14-15). However, Lippard (1983 p. 259) states that “Ecological art – with its emphasis on social concern, low profile and more sensitive attitudes towards the ecosystem – differs from the earthworks of the mid-1960s”.

Lippard discusses gardening as an art form, referring to artists who plant and harvest seeds and crops.

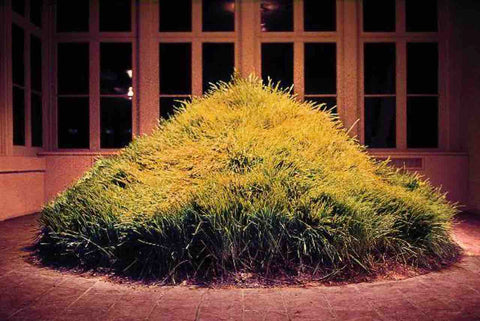

Lippard goes on to state that Land artist Robert Smithson once asserted that art degenerates as it approaches gardening, however, when asked by Hans Haacke how his (Haacke’s) work, Grass Grows, 1967-9 – a cone-shaped mound of earth with live grass which would grow during its exhibited period – differed from gardening, Smithson replied “by intent” (Lippard 1983 p. 259).

This is a seemingly contradictory statement by Smithson as Haacke’s Grass Grows does appear to be an extension of gardening. Therefore, was work that was made during this time, which was considered feminine or ecologically sensitive, more acceptable if it was made by a man because it was free from the gendered connotations associated with an art work made by a woman?

Agnes Denes’ Wheatfield

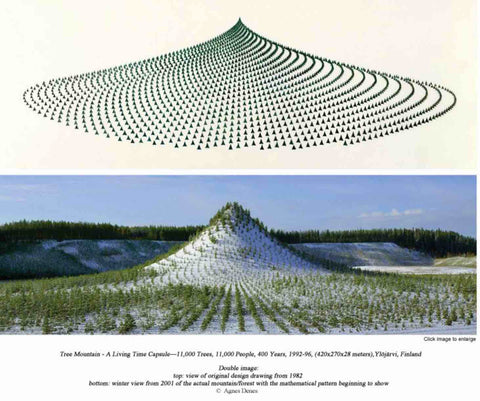

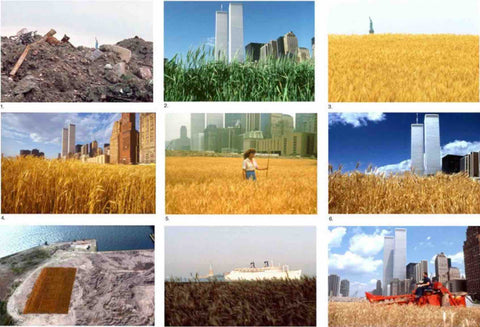

An artist particularly well known for her environmentally aware Land works is Agnes Denes. Most known for her large scale works made during the 1980s and 1990s (Wheatfield, a Confrontation, 1982: two acres of wheat planted for six months near Wall Street in New York City; and Tree Mountain: A Living Time Capsule, 1996: a monumental Earthwork made up of 11,000 trees which will last for at least four hundred years, located in Finland).

Denes was one of the first female artists who made work during the initial years of the Land Art movement.

In 1968, Denes first conceived Rice/Tree/Burial with Time Capsule. The work was a ritualistic and symbolic event which involved planting rice to represent growth, chaining trees to reference mankind’s interference with life and its natural processes, and burying a poem to symbolise humankind’s intellectual powers. Denes describes the burial of the work as marking humankind’s intimate relationship with the earth – a place for disintegration and passing, but also a place of regeneration and growth (Denes 2014).

British Male & American Female Artist Similarities

A comparison can be drawn between the work of female American artists and male British artists in that they both appear to approach working with the land with a gentler approach than the male American Land artists. Through reading feminist literature discussing Eco-feminism it can be seen that this term is often used as a way to separate the work of women into their own category. Therefore masking the environmentally aware work that male artists have created.

Size & Scale

Michael Heizer’s Double Negative

As discussed in the previous section, with reference to Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, many Land Art works were monumental in their size. Michael Heizer’s Double Negative , was completed in 1969 and consists of two gigantic rectangular trenches carved out of irregular cliff edges off of a tall, remote area of the desert in Nevada. This work was made by removing more than 200,000 tons of rock with the use of specialised heavy machinery. The work is 30 feet wide, 50 feet deep and 1500 feet long. The title of the work, Double Negative, refers to the empty void and man-made negative space that makes up the work (Govan 2014).

Alice Aycock’s A Simple Network of Underground Wells and Tunnels

In 1975, Alice Aycock exhibited A Simple Network of Underground Wells and Tunnels for the exhibition ‘Projects in Nature’ in an open meadow in New Jersey. This work, Aycock’s best-known piece, is made of concrete, wood and earth, and consists of an area approximately 28 by 50 foot, and 9 foot deep into the ground.

This work by Aycock differs to that of her male contemporaries in that it is built on a smaller scale so it can be accommodated by the visitor. Aycock’s work revolves around the theme of burial and fear; her work is designed to involve the visitor, and for each person’s unique experience to be part of the work.

Other works by Aycock follow a similar theme; Low Building with Dirt Roof (For Mary), made in 1973, is a structure that, like A Simple Network, can only be accessed by crawling through an underground structure. This work plays with the visitor’s sense of fear, anxiety and claustrophobia as above the structure is a mound of earth weighing 7 tons (Tuffnell 2006 p. 68).

Location

The choice of site was very important for Land artists; the remote locations which would rarely be accessed by the public meant that artists were moving away from and rejecting the standard ethos of the museum and gallery space. However, although Land artists wanted to revert from the institutional culture of the gallery, their work needed to be seen to receive recognition and critical acclaim for their future projects to be funded, and for their own personal wealth to increase. This meant that most Land Art works (or the works that we are aware of today) were heavily documented through photographs.

Water De Maria’s Lightning Field

Although Land Art can be considered to be public art due to its external locations, during the 1960s and 1970s this was not always the intention of the artists. Walter De Maria (cited in Oliveria 1996 p. 34) once stated “isolation is the essence of Land Art,” with photography being the only access most audiences would receive.

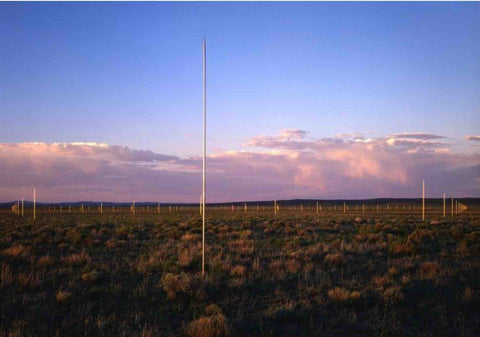

De Maria’s Lightning Field consists of four hundred stainless steel poles situated in a desert area in New Mexico in a kilometre squared grid formation designed to attract lightning. The area is known for its specific viewing conditions. Photographic documentation was controlled by the artist and only six visitors at a time are allowed to witness the potential Land Art.

When the Land Art movement was conceived, artists wanted to break free from the existing art world power structures; therefore, many visitors to the remote sites tend to be dedicated art experts and enthusiasts (Kastner and Wallis 1998 p. 15).

Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels

Most Land Art works are located in remote areas of America, isolated from civilisation. In 1976, Massachusetts-born artist Nancy Holt (1938-2014) completed Sun Tunnels, located in Utah’s Great Basin Desert. This work consists of four large tubes, made of cement and sand to mimic the desert’s floor, laid in an X arrangement.

This work is very well known within the Land Art movement due to its fame and location. Sun Tunnels is situated in the middle of the desert which takes a long time to get to through the necessary use of transport – it would be very hard to access this work on foot. To visit this work requires dedication. The drive from Salt Lake City takes approximately four hours, and the desert can be an unsafe place with unpredictable weather, lack of phone reception service, and no nearby help if anything were to go wrong (UMFA 2014).

To fully experience the work visitors are welcome to explore the inside of the cylindrical tunnels which provide shade from the sun and allow a new experience of the landscape and sky. The tubes are 18 foot long and 9 foot in diameter, with holes drilled through the surface to form perforations representing different constellations of stars, allowing visitors to look and for the sun to shine through. Sun Tunnels is a human-sized Earthwork designed to be used to observe the vast surroundings (UMFA 2014).

With regards to a gendered comparison of location, it seems that there were differences in the location of the Land Art works.

The monumental Earthworks made by the leading male artists were always situated in a deserted landscape far away from towns and cities. However, many of the works made by female artists were located within public viewing access.

For example: Mary Miss’s 1973 Battery Park Landfill, Manhatten; Alice Aycock’s Maze and Low Building With Dirt Roof (For Mary) located in New Kingston, Pennsylvania, and A Simple Network for Underground Wells and Tunnels, located in rural New Jersey in 1975. As I stated in Chapter One, female artists gained funding from museums, universities and international exhibitions – not private donors – therefore, it is assumed that there was stipulations that came with the public funding regarding the location of the work.

Through examining and discussing the Land Art of both male and female artists I have determined that there are few differences in the working methods and overall outcome of the work produced. The work of Richard Long and Robert Smithson is dramatically different, yet both men are coined as Land artists. Alice Aycock and Mary Miss’s work is large in size (granted, not on the same monumental scale as their male American counterparts) and fits the rubric of the Land Art movement. Yet their work – along with most other female Land artists – is generally forgotten about, or only very briefly referred to in comparison to the work made by men, when the movement is discussed in books and articles.

Although the connection of women with bodies is in some way a stereotypical one, it does seem that female Land artists were more likely to produce work connected to the body.

Women’s work tended to be body-sized or relating to the body, allowing visitors to often participate in the work itself, creating a sense of intimacy.

However, I will state that through considering the art made by women during this era, it does not seem that female artists wished to associate themselves with the gendered stereotype of women as nature whilst men are culture. Women disengaging themselves from the stereotypical feminine associations is noted by Boettger (2002 p. 149) who states that female artists of the 1960s and 1970s actively rejected the female-nature coding, and instead attempted to become part of the “artist=male” equation.

The Language Used to Describe Earthworks

Whilst it was men making the first Land works, it is noted by Thebaut and Upper (2010 p. 37-8) that these Earthworks were “marked by a feminization of the land through the male gaze”, as the male artists dominated “the ‘virgin ground’ that lay quietly, waiting to be imprinted by man.” The ‘male gaze’ is a concept presented by Laura Mulvey in the essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975). Here, Mulvey states that in films, women are objects to be gazed upon by the camera, and thus by the target audience of films – heterosexual men.

Through art reviews and interview accounts, it can be said that male Land artists saw the land as a place to be dominated. Michael Heizer referred to remote stretches of land as “un-raped, peaceful religious space[s]” (Beardsley 2006 p.13), whilst Claes Oldenburg (cited in Boettger 2002 p. 17) referred to the land as the “virgin ground”.

The concept of man dominating the female earth could be a contributing factor to the lack of female Land artists in the late 1960s.

As gender equality was only being realised at this time, it would not have seemed fitting for a woman to undertake such a ‘manly’ pursuit. Suzaan Boettger (2002 p. 148) notes that due to women’s traditional urban socialization during the mid-twentieth century, the typical wilderness of Earthwork locations were a formidable place for women to be. There was a precedent for the lone man, or cowboy, wandering the desert in America, however, none for women.

The oppositional dualism of Nature and Culture is further discussed by Cirksena and Cuklanz (1992 p. 29), who state that the central opinion of radical feminists is that “men’s treatment of women and nature is violent”. The Land artists in the early years of the movement have been described as being “macho”, with men “recasting the land with ‘masculine’ disregard for the longer term”, being environmentally insensitive and arrogant (Kastner and Wallis 1998 p. 15; Boettger 2002 p. 148, Tuffnell 2006 p. 46).

The men making these initial Earthworks were physically fit and assertive, and the materials used to realise the epic projects required strength and heavy machinery to aid transportation.

Boettger (2002 p. 148) states that “the physical activities performed to create them [...] required aggression, strength and stamina – characteristics of a traditional male type of overt power that was termed macho”. I disagree with this statement by Boettger – although specialised machinery was required to make many of the Earth Works, anybody can drive a bulldozer, and physical strength to create the monumental works would not have been enough from either a man or a woman.

However, to be able to use the specialised machinery, funding (which, as I’ve previously discussed, was unavailable to many women) was essential.

Being A Female Artist But Wanting To Avoid The Feminist Association

During the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Alice Aycock, Mary Miss and Jackie Windsor were politically active in striving towards an egalitarian art world. However, when discussing their art work, all three were cautious of labelling their art as being ‘feminist,’ as it did not address issues of gender (Schwartz 2010 p. 415).

This, notes curator Alexander Schwartz (2010 p. 415), left the artists in a challenging political position. All three women were often (willingly) included in exhibitions, books and articles devoted purely to female artists, which greatly helped to increase their fame and recognition. However, this exposure also meant that their work (when associated with these specific exhibitions and texts) would be viewed in the category of ‘feminist’.

This was an issue for all working women artists at this time. Lippard (1995 p. 33) notes that when one of the first feminist artists groups WAR (Women Artists in Revolution) came about in New York during the late 1960s, she herself resisted being associated with the group because she had “made it as a person, not as a woman”.

Competing in a Man’s World

It seems that for a woman to be taken seriously and viewed on equal terms to men in whatever field she chose to pursue, she had to detach herself from the stereotypical ‘feminine approach’ to working. For a female artist this meant rejecting the traditional (and undervalued) feminine art making methods of craft, such as sewing, weaving, and embroidery. Means of making art that have historically been considered appropriate for subordinated and domesticated women.

This opinion concurs with Sharon Firestone’s (1970 p. 14) statement that for an individual woman to participate in male culture, in this case art, “they have to do so on male terms. […] Because they have had to compete as men in a male game.” Firestone (1970 p. 15) goes on to say that in order for a woman to be able to produce “true ‘female’ art” (an art work free from any male influence – Firestone notes that when women took part in art activities in the 19th century they painted a man’s idea of what a picture should look like), it would take a rejection of cultural tradition. As when a woman does take part in cultural activities in feminine way, “she has been put down and misunderstood, named by the (male) cultural establishment ‘Lady Artist.’ i.e. trivial, inferior.”

In the case of women creating Land Art works, this meant making work which followed the stereotypical connotations of woman being closer to nature – art work dealing with rituals, Mother Nature and Goddess myths. I make this statement because the best-known female Land artists attracting the most critical writing (Nancy Holt, Mary Miss, and Alice Aycock) did not directly approach their work in a stereotypically ‘feminine’ way. Whereas other female artists who did make Land work with concern for the environment (be it through minimal impact, performing rituals, or creating an ecological work to benefit the Earth) are often only briefly – if at all – referred to in Land Art survey books. Part of the reason these artists are the best documented is that their work was closest to that of their male contemporaries.

The Notion of ‘Great Art’

I would argue that female artists received far less attention than their male contemporaries due to the lack of gender equality during this era, rather than because of the quality of their work. In the radical 1968 essay ‘Scum Manifesto’, Valeria Solanas (1968 p. 12) angrily states that women are the true artists (as opposed to the historical association of man=artist). However, it is men – the “passive and incompetent, lacking imagination and wit” creatures with “a very limited range of feelings and […] perceptions, insights and judgements” – who are deemed to be the artists who create “Great Art”. This art is deemed to be great “because male authorities have told us so”.

Solanas, though dramatic and irritated in many of her statements, makes valid points regarding equality in the art world. ‘Great Art’ has been created by men throughout history, and it is men who have judged and approved that art.

The notion of ‘greatness’ is discussed by American art historian Linda Nochlin (1971 p. 158) who tells us that throughout history there have been no great women artists because making art and judging the quality of the work occurs in a social situation which has been determined by specific social institutions such as art academies, patriarchal society, and theories referring to “the divine creator”. And all of these situations tell us that the artist is male.

Isabelle Bernier (1986 p. 41-43) notes when a woman becomes associated with an art form her contribution is customarily seen as of a lower status than her male analogues. Bernier goes on to state that when a feminine art form is practiced by both sexes – for example, sewing and making couture – the lower status of the art form is reserved for women. Whereas the superior and more sophisticated level – haute couture, for example – is controlled by men.

During the 1960-70s, women were beginning to make an impact on the art world, and in the male-dominated movement of Land Art – where work was most famously made by, and generally funded by, men (with the exception of Virginia Dwan) – it is easy to see why women’s work has always received less recognition.

Land Art in Recent Years

In recent years, attempts to re-examine the Land Art movement to credit the overlooked female artists have begun. A recent Land Art exhibition, ‘Decoys, Complexes, and Triggers: Feminism and Land Art in the 1970s’, located at SculptureCenter in Long Island City, New York in 2008, looked at the work of many forgotten female Land artists. This exhibition was similar to male-oriented Land Art exhibitions as many of the works were presented in the forms of documentary evidence such as photography, films, texts and plans.

Reviews discussing this exhibition have had their gendered approaches. New York writer John Haber (2008) discusses how in the early years of Land Art “men were tearing the human landscape apart” whilst women were “building, saving, planting and growing.” This review is gendered in its nature, believing that it was only men that were creating Land Art works that cut into the Earth’s surface, whilst women were assuming their historical role of nurturing the Earth. This was not the case, however, as there were women (Holt, Aycock, Miss, and others) who were building into and onto the earth.

Also discussing the exhibition, New York art critic Jeffrey Weiss (2008 p. 131) states that what was ‘feminist’ about the exhibition was unclear: although the exhibition featured the work of only female artists, no wall texts explained what was actually feminist about the selected works.

Alexander Schwartz (2010 p. 416) notes that female artists of this era would often be arbitrarily grouped together because of their gender, regardless of the fact that they might have little else in common. This is still true regarding recent receptions of Land Art as female artists are often discussed together in a small section of the books (Kastner and Wallis 1998; Beardsley 2006; Boettger 2002; Tuffnell 2006) dedicated to the movement.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to discuss the gender imbalance within Land Art in order to discover why women have historically been the less known sex within the movement. I approached this study with a revisionist approach, using feminist theories that discuss nature and the landscape as an interpretative framework. Through this methodology, I have been able to illustrate some of the reasons why women were marginalised from the production and reception of Land Art.

Through comparing the different working methods and outcomes of male and female Land artists it can be seen that there are not significant differences in the Land Art produced. The scale of the works is the biggest differing factor concerning gender. Men’s work in comparison to women’s is built on a monumental scale. I have come to conclude that there are various branches of Land Art that can be considered as part of the movement.

Categorically and without a doubt, the best known, most discussed and documented branch of the movement is the monumental works made by the male American Land artists, generally situated in deserted areas far away from human population. However, other aspects of the movement exist – the ephemeral and sometimes non-existent conceptual work made by British artists Richard Long, Hamish Fulton and Andy Goldsworthy are, also very well known. Through a literature search, it can be determined that ecologically sensitive Land Art is the least discussed and renowned branch of the movement – and coincidentally, the area of the movement where women were most prominent.

I would argue that because of the historical associations that connect women with nature and men with culture that no matter what work a female artist made during the Land Art proper years, she would have still received less recognition due to her sex and the gendered social constructs that came with being a woman at the time.

Bibliography

Articles

Agarwal, B. (1992) “The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India” Feminist Studies (Vol. 18 No. 1) pp. 119-158.

Archambault, A. (1993) “A Critique of Ecofeminism” Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cahiers De La Femme (Vol. 13 No. 3) pp. 19-22.

Bernier, I. (1986) “In the Shadow of Contemporary Art” in Robinson, H (ed) (2001) Feminism – Art – Theory Blackwell Publishing, pp.41-43.

Boettger, S. (2004) “Behind the Earth Movers” Art in America (Vol. 92 No. 4) pp. 54-63.

Boettger, S. (2008) “Excavating Land Art by Women in the 1970s” Sculpture (Vol. 27 No. 9) pp.39-45.

Boettger, S. (2012) “This Land Is Their Land” Art Journal (Vol. 71 No. 4) pp. 125-129.

Brookner, J. (1992) “The Heart of Matter” Art Journal (Vol. 51 No. 2) pp. 8-11.

Bryan-Wilson, J. (2012) “Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974” Artforum International (Vol. 51 No. 3) p. 269.

Cirksena, K. and Cuklanz, L. (1992) “Male is to Female As ____ Is to _____: A Guided Tour of Five Feminist Frameworks for Communication Studies” in Rakow, L (ed) (1992) Women Making Meaning Routledge, pp.18-44.

Chave, A. (1990) “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power” Arts Magazine 64 (No. 5) pp. 44-63.

Chodorow, N. (1974) “Family Structure and Feminine Personality” pp. 43-66, In: Zimbalist, M (1974) Woman, Culture, and Society Stanford University Press.

Constable, R. (1969) “The New Art: Big Ideas for Sale” New York Magazine (10 March 1969) pp. 46-49.

Coughlin, M. (2005) “Landed” Art Journal (Vol. 64 No. 2) pp. 105-109.

Duncan, C. (1989) “The MoMA’s Hot Mamas” Art Journal (Vol. 48 No.2) pp.171-178.

Firestone, S. (1970) “(Male) Culture” in Robinson, H (ed) (2001) Feminism – Art – Theory Blackwell Publishing, pp.13-17.

Glueck, G. (1968) “Moving Mother Earth” New York Times (6 October 1968) p. 38.

Griscom, J. (1981) “On Heading the Nature/History Split in Feminist Thought” Heresies #13 Earthkeeping/Earthshaking: Feminism & Ecology (Vol. 4 No. 1) pp. 4-9.

Hess, T. (1974) “The Condemned Playgrounds of Robert Smithson” New York Magazine (3 June 1974) pp. 88-89.

Krauss, R (1979) “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”. October (Vol. 8) pp.30-44.

Krauss, R (1973) “Sense and Sensibility, Reflection on Post ‘60’s Sculpture” Artforum.

Lippard, L. (1970) “The Art Workers’ Coalition: Not a History” Studio International (Vol. 180 No. 927) pp. 171-9.

Lippard, L. (1980) “Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s” Art Journal (Fall/Winter 1980) pp. 362-365.

Lippard, L. (1983) “Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory” In: Kastner, J and Wallis, B (1998) Land and Environmental Art Phaidon pp. 258-9.

Malone, T. (2013) “Judy Chicago’s best photograph: woman and smoke” The Guardian, UK, 17 October 2013, Available From: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/oct/17/judy-chicago-best-photograph-woman-smoke (March 2014).

McDonagh, D. (1968) “Art’s New Earthmen” Financial Times (No. 42, 696. 14th November 1968) pp. 3.

Moore, H. (1988) “The Cultural Constitution of Gender” in Polity (ed) (1994) The Polity Reader in Gender Studies Polity Press pp.14-21.

Mulvey, L. (1975) “Visual Please and Narrative Cinema” Screen (Vol. 16 No. 3) pp. 6-18.

Nicolacopoulou, M. (2012) “Ben Tufnell on Nancy Holt and Land Art” San Francisco Arts Quarterly (Issue 10) pp. 30.

Nochlin, L. (1971) “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” In: Nochlin, L (1989) Women, Art, and Power: And Other Essays Westview Press, pp. 147-158.

Ortner, S. (1972) “Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?” Feminist Studies (Vol. 1 No. 2) pp. 5-31.

Owens, C (1979) “Earthwords” October (Vol. 10) pp.120-130.

Perreault, J. (1968) “Long Live Earth!” Village Voice (Vol. 14 No. 1) p. 17.

Perreault, J. (1969) “Nonsites in the News” New York Magazine (24 February 1969) pp. 44-46.

Roach, C. (1991) “Loving Your Mother: On the Woman-Nature Relation” Hypatia (Vol. 6 No. 1) pp. 46-59.

Sanders, P. (1992) “Eco-Art: Strength in Diversity” Art Journal (Vol. 51 No. 2) pp. 77-81.

Schumacher, D. (1997) “Refiguring Nature: Women in the Landscape” Art Papers (Vol. 21) p.47.

Schwartz, A. (2010) “Mind, Body, Sculpture: Alice Aycock, Mary Miss, Jackie Winsor in the 1970s” in Butler, C and Schwartz, A (ed) (2010) Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art Museum of Modern Art pp. 413-425.

Solanas, V. (1968) “Scum Manifesto” in Robinson, H (ed) (2001) Feminism – Art – Theory, Blackwell Publishing, pp.12-13.

Soper, K. (1996) “Nature/’nature’” In: Kastner, J and Wallis, B (1998) Land and Environmental Art Phaidon pp. 285-287.

Spens, M. (2013) “Patricia Johanson: The World as a Work of Art” Studio International New York, Available From: http://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/patricia-johanson (April 2014).

Thebaut, N. and Upper, E. (2010) “Earth Movers: Quaking up Land Art’s Legacy of Feminism” Bitch (No. 48) pp. 36-42.

Tillim, S. (1968) “Earthworks and the New Picturesque” Artforum (Vol. 7 No. 3) pp. 43-44.

Weiss, J. (2008) “On the road: Jeffrey Weiss on land art today” Artforum International (Vol. 47 No. 1) p. 131.

Wittig, M. (1980) “The Straight Mind” in Robinson, H (ed) (2001) Feminism – Art – Theory Blackwell Publishing, pp.37-41.

Books

Adams, S. and Gruetzner Robins, A. (eds) (2000) Gendering Landscape Art Manchester University Press.

Battersby, C. (1989) Gender and Genius The Women’s Press.

Beardsley, J. (2006) Earthworks and Beyond 4th edition Abbeville Press Publishers.

Boettger, S. (2002) Earthworks Art and the Landscape of the Sixties University of California Press.

Boetzkes, A. (2010) The Ethics of Earth Art, University of Minnesota Press.

Burgett, B. (1998) Sentimental Bodies: Sex, Gender, and Citizenship in the Early Republic Princeton University Press.

Burgin, V (1969) “Situational Aesthetics” in: C. Harrison & P. Wood, (eds) (1997) Art in Theory 1900-1990 An Anthology of Changing Ideas Blackwell Publishers Ltd pp.883-885.

Conan, M. (ed) (2007) Contemporary Garden Aesthetics, Creations and Interpretations Dumbarton Oaks.

Crimp, D (1993) On the Museums Ruins The MIT Press.

Foster, H. and Krauss, R. and Bois, Y. and Buchloh, B. and Joselit, D. (2011) Art Since 1900 second edition Thames & Hudson.

Grand, J. (2004) Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists State University of New York.

Goldsworthy, A. (2001) Midsummer Snowballs H.N. Abrams.

Greenberg, C (1960) Modernist Painting. In: Harrison, C and Wood, P (eds) (1997) Art in Theory 1900-1990 An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, pp.754-760.

Hildebrand, A (1907) The Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture. Translated by M, Mayer & R. Morris Ogden. G. E Stechert & Co.

Jager, N. (ed) (1970) Earth Art The Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art.

Kastner, J. and Wallis, B. (1998) Land and Environmental Art Phaidon.

Kheel, M. (2008) Nature Ethics: An Ecofeminist Perspective Rowman & Littlefield.

Lessing, G (1766) Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry. Translated from German by E.C. Beasley, 1853. Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans.

Lippard, L. (1995) The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Feminist Essays on Art The New Press.

Morris, R (1969) “Notes on Sculpture 4: Beyond Objects” in: C. Harrison & P. Wood (eds) (1997) Art in Theory 1900-1990 An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Blackwell Publishers Ltd pp.868-873.

Oliveira, D. (1996) Installation Art Smithsonian.

Phelan, P. (1993) “Unmarked: The Politics of Performance” Routledge .

Giddens, A. and Held, D. and Hillman, D. and Hubert, D. and Seymour, D. and Stanworth, M. and Thompson, J. (eds) (1994) The Polity Reader in Gender Studies Polity Press.

Robinson, H. (ed) (2001) Feminism – Art – Theory Blackwell Publishing.

Samuels, S. (1992) The Culture of Sentiment: Race, Gender, and Sentimentality in 19th-Century America Oxford University Press.

Serra, R (1990) “The Yale Lecture” in: C. Harrison & P. Wood (eds) (1997) Art in Theory 1900-1990 An Anthology of Changing Ideas Blackwell Publishers Ltd pp.1124-1127.

Smithson, R (1972) “Cultural Confinement” in: C. Harrison & P. Wood (eds) (1997) Art in Theory 1900-1990 An Anthology of Changing Ideas Blackwell Publishers Ltd. pp.946-948.

Tuffnell, B. (2006) Land Art Tate Publishing.

Websites

Archives of American Art (2014) “Dwan Gallery (Los Angeles, Calif. and New York, N.Y.) records, 1959-1971” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA, Available From: http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/dwan-gallery-los-angeles-calif-and-new-york-ny-records-6056 (Feb 2014).

Aycock, A. (2012) “Alice Aycock” Alice Aycock, USA, Available From: http://www.aaycock.com/ (July 2014).

Denes, A. (n.d) “Rice/Tree/Burial with Time Capsule” Agnes Denes, New York, Available From: http://www.agnesdenesstudio.com/works2.html (September 2014).

Govan, M. (2014) “Michael Heizer” Dia Art Foundation, USA, Available From: http://www.diaart.org/exhibitions/introduction/83 (July 2014).

Green Museum (2010) “Betty Beaumont: Ocean Landmark” Green Museum, California, Available From: http://greenmuseum.org/content/work_index/img_id-382__prev_size-0__artist_id-37__work_id-75.html (September 2014).

Haber, J. (2008) “Down to Earth – Decoys, Complexes, and Triggers: Feminism and Land Art” Haber Arts, New York, Available From: http://www.haberarts.com/decoys.htm (August 2014).

Johanson, P. (2013) Patricia Johanson Patricia Johanson, US, Available From: http://patriciajohanson.com/ (March 2014).

Johnson, K. (2001) “Sidney Tillim, 76, Art Critic and Historic Scene Painter” The New York Times, New York, Available From: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/08/20/arts/sidney-tillim-76-art-critic-and-historic-scene-painter.html (September 2014).

King County Archives (2014) “Earthworks: Land Reclamation as Sculpture” King County, Seattle, Available From: http://www.kingcounty.gov/operations/archives/exhibits/Earthworks.aspx#Pepper (March 2014).

MacQueen, K. (2012) “Shifting Connections: Hans Haacke” Bomb Magazine, Available From: http://bombmagazine.org/article/6363/ (September 2014).

MOCA (2010) “Ana Mendieta” The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California, Available From: http://www.moca.org/pc/viewArtWork.php?id=87 (September 2014).

MOMA (2014) “Richard Long” Museum of Modern Art, New York, Available From: http://www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O%3AAD%3AE%3A3591&page_number=1&template_id=1&sort_order=1 (July 2014).

Smith, L. (2003) “Beautiful, Sublime” The University of Chicago, Chicago, Available From: http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/beautifulsublime.htm (September 2014).

Stephens, E. (n.d.) “Beth and Annie in Conversation, Part One: Interview with Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison” Total Art Journal, Available From: http://totalartjournal.com/archives/1940/beth-and-annie-in-conversation-part-one/ (September 2014).

Tarasen, N. (2014) “Double Negative” Double Negative, USA, Available From: http://doublenegative.tarasen.net/double_negative.html (July 2014).

Tate (2014) “Land Art” Tate, UK, Available From: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks?ap=1&gm=429&wp=1&ws=date&wv=grid (September 2014).

UMFA (2014) “Sun Tunnels self-guide” UMFA Utah Museum of Fine Arts, USA, Available From: http://umfa.utah.edu/suntunnels_selfguide (July 2014).

VAGA (2014) “Spiral Jetty” Robert Smithson, USA, Available From: http://www.robertsmithson.com/earthworks/spiral_jetty.htm (September 2014).

Yates, M. (2013) “Marie Yates” Marie Yates, UK, Available From: http://www.marieyates.org.uk/ (April 2014).

© Kate Chesters Art 2020

1 comment

WOW – thank so so much for this… incredible research and invaluable information…