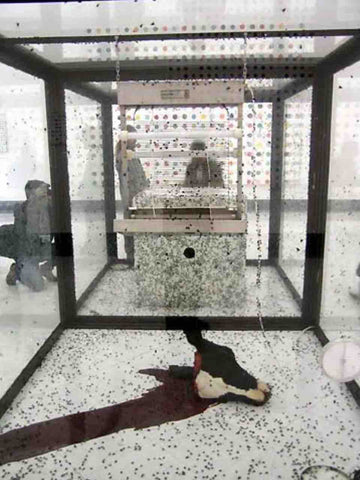

I will examine the ways in which Young British Artist Damien Hirst, born in 1965, addresses death and mortality in his work through the use and presentation of decaying materials, focusing particularly on one of his most famous works, ‘A Thousand Years’ . This work involves the observation of the life cycle processes taking place within a glass box involving thousands of flies feeding from a decaying cow’s head (the flies in fact fed from a sugar-water solution). The rotting head of the cow within ‘A Thousand Years’ was quickly replaced after being first displayed, changing it from a real cow’s head to a taxidermied head, to prolong the lifespan of the piece.

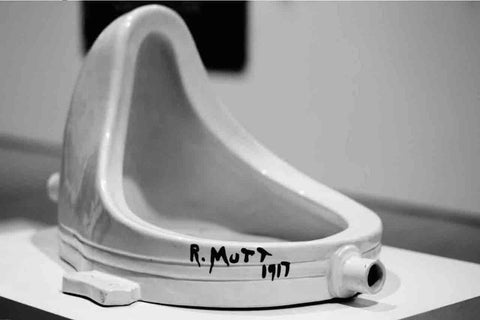

Through the arguments of critical writers I will analyse what effect this has on the legitimacy, meaning, intent and originality of the piece. I will discuss this matter further through Joseph Kosuth’s Art After Philosophy, concerning Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ - a work of art that has been replicated numerous times due to the fact it was lost soon after its creation, and it is the first acknowledged ‘readymade’ work of art.

Damien Hirst

Having decided to make the piece whilst at Goldsmiths, Hirst now regards ‘A Thousand Years’ to be one of the most important works of his career. The piece took two years to plan, at which time Hirst had to borrow money off friends to finance the work. It was through planning the piece that the artist decided he wanted to create a “life cycle in a box”. As American art critic Jerry Saltz notes in the article More Life: The Work of Damien Hirst, within the strong and formal structure of the virtrine “every element affects every other part of the system, as chaos and order blur”. The majority of works throughout the history of art have explored themes of life and death through the use of imagery as visual metaphors. Hirst, however, literally makes a performance of life and death, and presents it to the viewer as “Death in a Box”.

Life and Death

‘A Thousand Years’ is a large-scale indoor installation which involves a decaying cow’s head being fed on by flies and an insect-o-cutor (a device used to eliminate flies from restaurant and kitchen areas) encompassed in a large glass case. This enclosed vitrine was the setting for the cycle of life and death, for, as long as the cow’s head remained intact - seemingly the life force of the entire piece - then the pattern could continue. The clever use of the title ‘A Thousand Years’ tells the viewer that the work will last for not an eternity, but a very long time; however, by encasing the work within a tank, Hirst gives the impression that piece has a strength and durability that will last forever. During the period of exhibition, twenty thousand maggots were introduced to the work every week through a tube, and at the end of the exhibition the same tube would deliver insecticide. The combination of aesthetics – the decaying cow’s head, the awareness of moving through time, the encouragement of new life, but also the termination of it – give the work a layered depth of substance and meaning which touch on the borders of life and death and the live and theatrical.

The Question of Authenticity

It was however, a sugar and water solution rather than the rotting cow’s head which the flies fed upon. For Hirst to use a real cow’s head for the entire duration of ‘A Thousand Years’, the carcass would eventually begin to rot away, therefore transforming the aesthetic experience of the work, meaning that the physical appearance would gradually alter, and the work would one day cease to exist. Due to issues of practicality and longevity – the cow’s head needed changing approximately every 72 hours – and controversy surrounding the use of a real cow’s head, the head was soon changed and replaced by a taxidermied version made by English artist Emily Mayer. Taxidermy is the process of preparing, stuffing and mounting the skins of dead animals for display purposes. Mayer had to make several of the cow’s heads as they were changed periodically by Hirst. This exploit provokes the debate of whether the preservation of fragile or unstable works affects the meaning of the art; the definition and significance of what constitutes to be an original piece of art; and the authenticity of the work. For art works like ‘A Thousand Years’ which rely on conservation (replacing and/or updating decaying elements) to remain intact, this begins to make the process nonscynchronous with the original method of production.

The Originality of an Artwork

An art work’s importance can be measured through written instructions, certificates and contractual arrangements in order to determine its significance concerning value and rarity in relation to market value and a collector’s worth. The originality of a work refers to the circumstances of conception and if the artwork is to be viewed as a property in itself, or as being property of the artist. Concerning the ‘readymade’ art objects of Duchamp and other contemporary artists, the object must first be chosen for whatever reason the artist deems practical, then recontextualized in order to communicate the artists ideas. Considering Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ was duplicated no less than fifteen times, it seems peculiar that galleries would want to pay large sums of money for such a highly replicated object. However, many galleries and art collectors would pay vast amounts to own the original ‘Fountain’, even though there are thousands of other urinals available throughout the world. It is the intrinsic character of Duchamp’s urinal and the fact that so many other purchasers are willing to pay a high price, that the commercial value of the contemporary piece is so great.

Authenticity and Authorship

Authenticity and authorship is determined through the artist’s connection and participation towards the art works construction and ongoing existence. However, authorship concerning the artist’s ongoing connection to the work, regarding maintenance and changes made (for example, the cow’s head being changed on a regular basis by gallery staff) can be organised by means of a series of specific or negotiated decisions made through the artist.

Legal Ownership of an Artwork

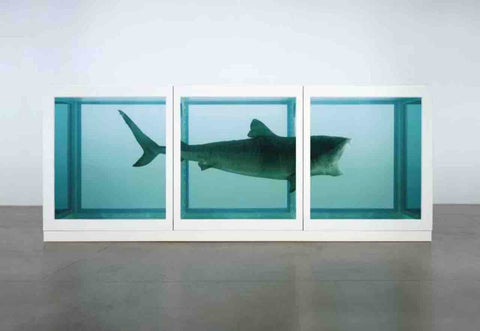

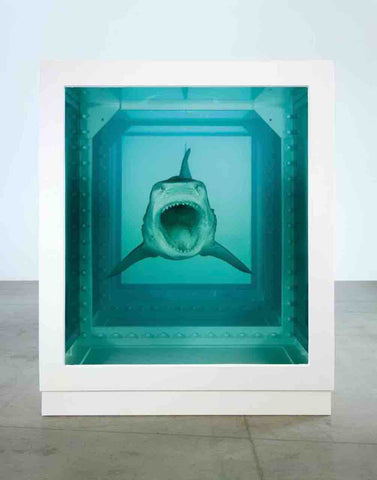

The relationship between the artist and an art work, and the buyer or sponsor of an art work brings into question the issue of who has authority over the work. Until the nineteenth century, artists relied on patronage in order to make a living from making art. Throughout the twentieth century however, artists relied on the investments from art galleries and sponsorship from wealthy donors. In 1991, Damien Hirst made ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’ - a 14-foot long shark enclosed in a steel glass case filled with formaldehyde solution – a work sponsored by art collector Charles Saatchi. When the work was displayed at the Saatchi Gallery, Saatchi changed the displaying method that Hirst had originally planned; this frustrated Hirst, who in the biographical television documentary Damien Hirst: Thoughts, Work, Life said, “he [Saatchi] was paying for it, so it went the way he wanted it, and that really annoyed me”. Throughout history artists have been assisted with the creation of their works through manual or financial help; for example, the taxidermied cow’s heads were made by Emily Mayer because of her acute skill. This highlights that while the artist may have the original concept or idea for a work, unless the work is fully completed, paid for, and exhibited by the artist themselves in their own space, then they do not have full legal authorship over a work.

The Preservation of Art

To embody time through a decaying work of installation art, one must accept that temporality is an inevitable aspect in the process of degeneration - it is through the physical changes that take place within the work that time can be represented. As Robertson and McDaniel note, “time is measured and made manifest by change”; in order for the viewer to experience the full effect of performance or kinaesthetic art, one has to see the work unfold in live time to grasp the meaning and emotion of the piece. Representing time through a work of art generally means that the piece moves or uses media which creates the illusion of movement – static works such as the Dutch still life ‘vanitas’ paintings can generally only represent time through symbolization and suggestion, however literal aging still occurs through the slow physical decay of the paint and canvas - or, like in the case of ‘A Thousand Years’, the materials used in the piece remain in flux during the entire lifespan of the work. What we often consider to be ‘art’ is the happenings that occur between the event and the object. Victor Burgin describes the process of physical changes due to time within art works as “permanence [being] revealed as...a relationship and not an attribute”, clarifying that in order for an art work to be endurable and last for generations, support, maintenance and even remaking, is required to prolong the lifespan.

As Hirst’s cow’s head was changed regularly, it is the flies that are the constant remaining yet changing factors of the piece - it was noted that over sixty generations of flies had experienced the life cycles of birth, feeding, mating and death during the first installation period staged by Hirst.

Conceptual Art

Replacing or preserving art works to prolong their lifespan is not necessarily an issue in the opinion of Joseph Kosuth who, in his essay Art after Philosophy, discusses Marcel Duchamp’s ideas concerning “objets d’art” (meaning ‘art object’ in French). Reviewing the beginning of Modern art and Conceptual art, Kosuth notes that the actual physical aesthetics concerning a work of art are irrelevant, because it is the conceptual idea behind the artwork which is important. This is relevant concerning Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’, which was made in 1917, however soon went missing; it is not known whether the work was hidden, stolen, lost, or even made by Duchamp himself. Since the original piece was lost, fifteen authorised replicas have been produced, all signed by the artist. The recycling or use of pre-existing objects within art is known as appropriation, with Duchamp’s ‘readymade’ ‘Fountain’ works generally being considered to be the first successful and most notable within art.

Kosuth furthers this point, stating that years after the artwork has been made, “the artists’ intentions become irrelevant”, that it is not the actual art work or idea that is important within art, but merely that art is a “collector’s item”. Anything that occurs after the work has been made – for example, if the work is displayed in a different way or in a different venue – is not important because it is “an adoption of what...previously [existed]”. These statements describe that art works and their meanings are only relevant during the present time that they are made because they are significant and relate to the culture of that specific period.

Whilst the use of readymade objects has been practiced as an art form by Marcel Duchamp, Damien Hirst and many other artists, it is curious that art galleries and museums would accept this as a form of art, when there are issues of originality, longevity, the lack of the artist’s touch or skill and the possibility of reproduction.

The issue of replacing or updating something live is argued by Groys (2002, 212) who states that if a living thing can be reproduced or replaced, then the piece loses its “unique, unrepeatable lifespan, which is ultimately what makes the living thing a living thing”. Although Hirst’s original cow’s head was always dead, the fact that it is an organic material meant that it could naturally decay over time, therefore, replacing the natural head to the artificial changes the original narrative of the work.

Is It Art?

When considering the material matter of Hirst’s ‘A Thousand Years’ and ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’ (flies, cow’s head, maggots, shark), one might assume that these works could not be considered art, as direct representations of animals (alive or dead) are often found in natural history museums. American art philosopher George Dickie provides definitions of what constitutes to be a work of art in several essays written from 1969 onwards, each article written reformulating and redefining the writer’s previous definition. In each definition, Dickie is clear and precise in the execution of ideas and theories, explaining each term used so that the reader is in no doubt of the intended meaning. In the fourth version presented in The Art Circle, Dickie specifies art to be made by an artist and to be presented to the art world as a work of art. Anything presented otherwise is not a work of art. Therefore, an object that you would assume to be, and is, displayed in a natural history museum, in Dickie’s opinion, is not art. However, the fact that Hirst identifies himself to be an artist who makes works of art which are intended to be displayed in an art gallery, is what makes ‘A Thousand Years’ and ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’ valid works of art.

Intent and Meaning

In Immanuel Kant’s essay The Critique of Judgement, Kant states that art is different to science because it requires practical skill. However, even though to produce a work of art takes a sense of practice, it differs from craft or design, because art has no functional requirements. When this theory is applied to the issue of replacing the cow’s head in ‘A Thousand Years’, the preservation of the work does not matter because the gradual physical decay of the cows head is not functionally needed in order to portray the intent and meaning. Therefore it is acceptable to have the taxidermied copy because so long as the decay is aesthetically represented in some way, it is that which is important to the conceptual meaning of the work.

This point is furthered by Gordon Graham who recognises, when considering Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’, that it is not the physical presence of the urinal in a gallery space, but more the idea that there is a urinal in a gallery space, which makes the artwork controversial. Therefore, the aesthetic value of an art work is not attached to the physical piece, but more to the idea or concept behind it.

Substance over Style?

Through this analysis, the physical appearance of a work of art is relevant to only metaphorically display the artist’s intentions and ideas. The ready-made ‘Fountain’ of Duchamp’s is an everyday object which the artist contextualised and therefore valorised. If an artist refrains from physically transforming the object, reproduces numerous quantities of the object, or repairs and/or replaces parts of the art work, then the value of the work is brought into question. The status and value of a work is determined by the idea or conceptual process which is conveyed through selected images and objects by the artist. This therefore, in the opinion of Graham, suggests that physical art will one day be replaced by philosophy, just as the readymade art shifted the focus from artwork to artist, conceptual art begins to shift the emphasis from art to the idea.

2 comments

It was good that you mentioned how artwork is often preserved because of the importance of its originality and the circumstances of conception. I’m guessing if you have an area that has become significant because of its history, such as the civil war remnants, it would be wise to preserve them as well. I’ll keep this in mind in case I ever need to work with a preservation association for historical places in the future. https://burkittsvillepreservation.org/about-the-burkittsville-preservation-association/

It was an interesting reading, thanks for sharing.

In my opinion the real head cow conveyed also the idea of the limited resources available for that system to carry on with the cycles of life and death. It acted as a timer for the existence of that system, in a way similar to our sun.

Replacing the rotting head with taxidermy and sugar will alter the representation of that idea, don’t you think?

Cheers