In this article I will discuss the perishable nature of the work by earth artist Ana Mendieta, focusing specifically on, arguable her most famous works, the ‘Silueta Series’.

I will examine the need and reliance Ana Mendieta placed on documenting her performances, through the various media methods of photography and film, and the relationship between the documentation and the work itself.

The use and dependence of documentation through photography to capture the event of ephemeral artworks allows the question to emerge: what is the artwork and what is the documentation? Is the photograph an artefact of the event, an externally produced record where the event is the artwork, or is the work defined by the outcome of the procedure (the photograph or film) which emerged from the event itself? The distinction between the two lines of enquiry has the capacity to change the photographic/film documented evidence into a combined element or finished product of the work itself.

Ana Mendieta

Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) was a Cuban-born artist exiled to America during the Cuban revolution at the age of twelve. Mendieta is best known for her ‘Silueta Series’, a series of private performances which took place between 1973 and 1980 and explored the relationship between the artists’ body and the earth. The ‘Silueta Series’ began whilst Ana Mendieta was on a journey to Oaxaca, Mexico, with Hans Breder, a German artist with whom Mendieta had a decade-long relationship with, who assisted Mendieta in photographing her performances. Breder was originally Mendieta’s teacher at the University of Iowa, and he encouraged his students to document their ephemeral and site-specific art so they could have evidence of the work, in order for them to get their degrees.

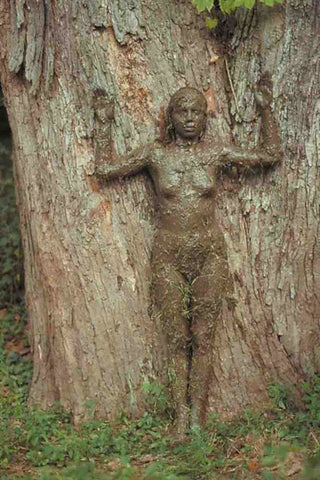

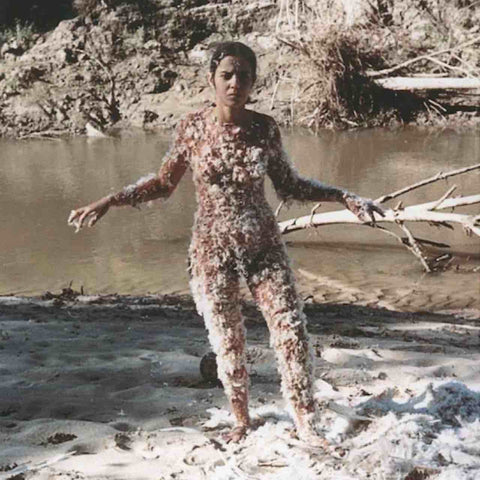

The performances by Ana Mendieta were usually site-specific and ephemeral – her works being washed, burned, reintegrated or melting away, eventually ceasing to exist - so they became known through the photographic documentation of the events exhibited in museums and galleries by the artist. In her body of work, Mendieta addresses a wide range of issues surrounding sexuality, spirituality, cultural displacement, feminism and identity.

Silueta Series

The image above shows an example of six of the works made for the ‘Silueta Series’; in one image a human figure has been twisted into shape by twigs; in another the red imprint of the artists body has been marked onto a white sheet, hung against the stone and plaster wall of an alcove; the third image shows the hollow indentation of Mendieta’s body with her arms raised within the shore of a waters edge, filled with a red dye, waiting for the water to fill the impression and wash away the colour, allowing the figure to metaphorically ‘bleed’.

The first Silueta by Ana Mendieta was performed in an ancient Zapotec tomb in Oaxaca, and shows the artist laying down on the floor of the site, surrounded and covered in flowers that appear to grow from her body. The ‘Silueta Series’ photographs show Mendieta’s body in communion with various landscapes, a process which the artist found ritualistic . Mendieta’s primary audience was a camera – the artist rarely performed in front of the public. The photographs taken capture the life and the breakdown of the Silueta’s and in most cases today, these documents are the only remaining traces of evidence that these works ever existed.

Is the Art Work the Live Performance or the Exhibited Documentation?

The use of photography within art has increased over the past century due to significant technological advances and the requirements from artists involved in various artistic practices that create their work away from the studio or gallery space. The photograph provides not only a new way of creating visual art, but also a revolutionised way of considering and representing time. What the photograph actually stands for can vary; the photograph can act as a secondary document; or as a substitute for the direct access to a particular art work that is unavailable for public viewing in a gallery space (site-specific Land Art for example); or the photograph is the culmination of the work or performance and therefore is the artwork. It can be unclear sometimes however what the artist’s aim is – the photograph can be presented as a component of the artist’s work, or it can be used as a vehicle for the actual documented work to be seen through.

The relationship between the artist and photographer is a crucial element to the work and how it is translated to the viewer. The interpretations made from a documented performance can be influenced by the intentions, ideas and aesthetics of whoever recorded the event. In an interview between Alice Maude-Roxby and Hans Breder, Breder tells of how he and Ana Mendieta would always discuss the translation of action into photography prior to the actual live event. This was very important for both photographer and performing artist to understand what was desired in the final outcome.

Photographic Documentation

In the journal article Presence’ in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation, Amelia Jones contends that in order to learn about performance art, the documentation is required for reflection to take place. Jones goes on to observe that “the body art event needs the photograph to confirm its having happened; the photograph needs the body art event” which shows that if an art work is to survive the test of time, both elements of presentation are needed in order for the work to be a success. This is an interesting hypothesis when balanced against the work of Ana Mendieta; the ‘Silueta Series’ is photographed at its point of loss and disintegration, therefore while the photograph provides evidence that the Silueta occurred, it also at the same time shows the absence of the Silueta just as equally - the photograph is the captured moment of unbounded space and time.

Live Performance and Documentation - Which is the Artwork?

There are issues however with documenting works that were once live; if the work was once viewed as a live performance, audience members at that time may have had a radically dissimilar experience to the work than if it was displayed in an alternative environment through different methods, for example, a live dance performance seen in a theatre being documented and shown in a gallery space as a video or photograph. Furthermore, using a photograph to represent a live performance captures only a single momentary shot and disregards the rest of the performance. Martha Buskirk recognises this contention, noting that if an art work is realised and/or made during a performance, then the physical qualities of the work cease to exist when it is disassembled or reproduced.

The Ontology of Performance

The photograph or film being a mere fragmentary record and not part of the work is argued by Phelan (1993, 146) who states that “performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance”. Phelan’s views are somewhat narrow in terms of accepting documentation in conjunction with live performance; Phelan goes on to note that ”the documentation of a performance then is only a spur to memory, an encouragement of memory to become present.”

Although Phelan’s views towards documentation are negative, this point argues that a performance can be merely documented because the bodily presence of the performer in the event is ontological – it is impermanent and it physically can never be completely reproduced. The performance itself is ephemeral, which metaphorically sits in opposition to the static, non-changing photographs and recordings which document it. Therefore the documenting photograph or film can be used, but only (in Phelan’s views) to remind audience members who viewed the original live performance of what they once saw.

Photographs can be a valuable reminder or witness of the event, however they do not show everything that happened. The experience of just seeing the photograph or film and not the live works itself would not have the same impact, for as Phelan notes; any attempt to save or preserve the performance changes the meaning of it. The documentation should be understood to be a medium for the work to be remembered.

Art critic Lucy Lippard (1969, 180) takes a similar stance to Phelan’s views, arguing that “temporary art exists for less time but is no less accessible by photographic record.” Performance art, if not documented, can only be revisited primarily through the memory of those present at the time and their accounts of the event, and secondly through word of mouth. Media documentation can have the consequence of diminishing the original emotion and effect of the performed event, therefore preventing the viewer from fully engaging with the meaning, and giving the false impression that the performance continues after the piece has come to an end.

Documentation as an Instrument of Site-Specific Work

The use of documentation within site-specific performative works can be seen as a combined element of the procedure of the performance, something which Nick Kaye (2000, 32) analyses as being “an instrument of site-specific work”. Kaye argues that through site-specific performance work, the artist’s body becomes the site of the work – the land being the recipient of the performative action, and the action of the performance being the ephemeral mark of contact to the earth. These impermanent works are generally left to be dismantled by nature (ice that melts away, soil becoming overgrown, sand that falls apart etc.), causing them to become a device of transience. Documentation of site-specific performance works occurs because it is incorporated as part of the art work and the culmination of it, the photograph acting as a witness to the live event.

This view is supported by Auslander who notes that the issue of the documentation of live performances has only come about within the past 100 to 150 years, due to the advance of recording technologies. Before this era, the term ‘live’ within performance did not exist, because there were no means of making it anything other than ‘live’. The expression of “liveness” within performance art has only come about due to the possibility of technical reproduction. It is through this realisation that Auslander rejects Phelans claims that “to the degree that live performance attempts to enter into the economy of reproduction it betrays and lessens the promise of its own ontology”, because the notion of live performance “can only exist within an economy of reproduction”. Therefore, what we conceive as being ‘live’ will always be subject to mediatisation, because it is from the use of media technology that we are even aware of the concept of being ‘live’.

Documentation Incorporated Into Artistic Practice

There will always be a relationship connecting the processes of documentation to the site-specific event itself, whether being an actual part of the work or subsequent to it, with the site of the art work not being assumed to simply be present to performance, or absent from documentation. This is agreed by Maude-Roxby who states that the document of a performance is not the actual art work, but it is neither merely a photograph or film; it holds a position in between the two, and there is no simple means of determining where any particular example can sit on that spectrum. This changes the significance of the photographic or film documentation from being a historical artefact to being an incorporated part of the artistic practice. Every documentary photograph, video and film is a permanent artefact of the presentation, staging, visual object or event that once took place.

In terms of the work of Ana Mendieta, there is a co-existence of the permanent and eternal, and the performative and ephemeral. The importance and value of the live work in association to the documented work, in the opinion of Martha Buskirk is that it does not really matter whether the photographs or films factually depict the performance that originally took place, or whether a performance took place at all and the photographs are merely staged to give that impression, because that is how the artist has chosen to represent their work.

Bibliography

Books:

Auslander, P. (1999) Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. London: Routledge.

Beardsley, J. (1984) Earthworks and Beyond. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers.

Boetzkes, A. (2010) The Ethics of Earth Art. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Burgin, V. (1969) A source of information. In: Harrison, C. & Wood, P, ed. 2002. Art in Theory 1900-2000. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Buskirk, M. (2003) The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art. Massachusetts, USA: The MIT Press.

Clearwater, B. (1993) Ana Mendieta. Florida, USA: Grassfield Press.

Dickie, G. (2001) Art and Value. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Groys, B. (2002) A source of information in: Jones, A. & Heathfield, A. ( 2012) Performance Repeat Record. Bristol: Intellect.

Guglielmino, G. (N.D) How To Look At Contemporary Art. London: Umberto Allemandi & C.

Graham, G. (2005) Philosophy of The Arts. Oxon: Routledge.

Jones, A. (1998) Body Art / Performing The Subject. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Kant, I. (2007) The Critique of Judgement. New York: Cosimo.

Kaye, N. (2000) Site Specific Art; Performance, Place and Documentation. London: Routledge.

Kosuth, J. (1969) A source of information. In: Harrison, C. & Wood, P, ed. 2002. Art in Theory 1900-2000. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Licht, I. (1975) A source of information. In: Loeffler, C. & Tong, D, ed. 1989. Performance Anthology. San Francisco: La Mamelle, Inc.

Lippard, L. (1967 and 1969) A source of information. In: Alberro, A. & Stimson, B, ed. 1999. Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology. London: The MIT Press.

Maude-Roxby, A, ed. 2007. Live Art on Camera. Southampton: John Hansard Gallery.

Molderings, H. (1984) A source of information. In: Battcock, G. & Nickas, R. Ed. 1984. The Art of Performance: A Critical Anthology. New York: E.P Dutton.

Phelan, P. (1993) Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, Routledge, New York.

Robertson, J. & McDaniel, C. (2010) Themes of Contemporary Art: Visual Art after 1980. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Internet:

Mendieta, A. (1973-77) Silueta Works in Mexico. [electronic print] Available at: <http://www.moca.org/pc/viewArtWork.php?id=87> [Accessed 19 November 2012]

Journals:

Auslander, P. (2006) The Performativity of Performance Documentation. Performing Arts Journal, 28(3), p.1-10.

Auslander, P. (1997) Against Ontology: Making Distinctions between the Live and the Mediatized. Performance Research. 2(3). P.50-55.

Cabañas, K. (1999) Ana Mendieta: “Pain of Cuba, Body I Am”. Woman’s Art Journal. 20 (1) p. 12-17

Forte, J. (1988) Women’s Performance Art: Feminism and Postmodernism, [e-journal] 40 (2) p. 233-235. Available through: JSTOR website <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3207658> [Accessed 13 Novermber]

Jones, A. (1997) Presence’ in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation. Art Journal, 1997, 56(4) p.16.

McMahon, J. (2000) The Script of Sensation. [e-journal] 21 (3) p.67-77. Available through: JSTOR website < http://www.jstor.org/stable/40244618>